Shahriar Hossain: Coming Home

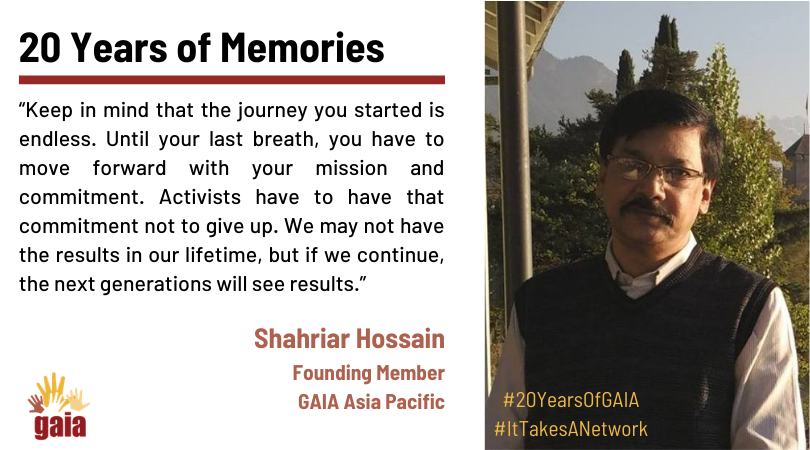

“Keep in mind that the journey you started is endless. Until your last breath, you have to move forward with your mission and commitment. Activists have to have that commitment not to give up. We may not have the results in our lifetime, but if we continue, the next generations will see results.”

– Dr. Shahriar Hossain

The 1990s were not the best of times for Bangladeshi environmentalist Dr. Shahriar Hossain. The decade saw the then thirty-something activist receiving death threats, dodging attempts on his life, and going into exile.

“In 1992-1993, we were running a campaign on a national plastic bag ban in Bangladesh,” Dr. Shahriar recalled, referring to the early work of ESDO or Environmental and Social Development Organization, which he had founded the year prior.

As the head of the organization, he was at the forefront of the campaign, and inevitably, he got the ire of the industry. “People tried to kill me several times. I requested for protection from the government, but I was denied support. I was forced out of the country instead,” he said.

Dumbfounded that the country for which he served as the youngest freedom fighter during the 1971 Bangladesh liberation war had turned its back on him, the gentle, soft-spoken Dr. Shahriar packed his suitcase and left for the United States in 1994—carrying with him his vision, but leaving behind his loved ones.

“It was very difficult for me. I left behind my family in Dhaka. My children had to stay at home and not go to school for a year. My team in Bangladesh suffered but they continued their work. It was hard, but the good thing is that many came forward to support,” he recalled.

In the United States, Dr. Shahriar was provided the support and protection his own country had denied him by the Advocacy Institute of Washington, an organization that trained lobbyists in how to effectively pursue their causes. Its co-founder—David Cohen—took Dr. Shahriar under his wing.

“David was like a father to me. He helped me mentally and supported me financially,” Dr. Shahriar shared, adding that it was through Mr. Cohen that he got jobs while in exile.

Dr. Shahriar soon found himself working as International Fellowship Coordinator for the Advocacy Institute. Later he became a faculty member at the George Washington University teaching social ecology, and a contributor to the Washington Post.

But it was his work at the Advocacy Institute that proved seminal for the formation of what is now a global network of organizations and activists fighting for a toxic-free world—the Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives (GAIA).

“During my time at the Advocacy Institute, I learned so much about incineration processes and issues. At the time, I was working in communities. In Delaware, there were communities within the incinerator facilities,” Dr. Shahriar said.

According to Dr. Shahriar, the incinerator industry had its heyday in mid- to late-1990s, peaking in the early 2000s. “It was not an easy time. Everybody was moving toward incineration. The incinerator companies were targeting Asia, Latin America, and Africa,” he shared.

Fortunately, Dr. Shahriar’s work at the Advocacy Institute involved organizing fellowships for environmentalists and activists from around the world, and Mr. Cohen gave him the space to do his own advocacy. He used these fellowships to talk to the fellows about incineration.

“The fellows showed interest in taking on the issue. We thought of creating a global movement. We thought it was high time to talk to the developing nations and bring the activists together. We thought about raising one voice together—one voice saying, ‘No to incineration!’” Dr. Shahriar said, adding that during those times, some of the fellows already had local campaigns against incinerators.

Dr. Shahriar recalled Ricardo Navarro, Paul Carter, Neil Tangri, Jayakumar Chelaton, and Bobby Peak as among the first ones to respond positively to the idea.

These conversations were followed by a flurry exchange of letters between and among Dr. Shahriar and the fellows. “There was no email yet at the time. We had to rely on fax machines and letters, but fax was not accessible in some countries, so we mostly relied on letters,” Dr. Shahriar shared.

And in December 2000, after years of dreaming together and organizing, the thinkers came together in Durban, Africa, and GAIA (originally Global Anti-Incineration Alliance) was born.

Unfortunately, Dr. Shahriar did not make it to the gathering. “I sent a message which was conveyed in the meeting,” he said.

The year after, in 2001, Dr. Shahriar was back in Bangladesh. “The government invited me back and committed to support my plastic bag movement,” shared Dr. Shahriar, adding that being back home gave him “a feeling of rebirth and return to [his] freedom land.”

And true to their word, the Bangladeshi government banned plastic bags in 2002, making Bangladesh the first country in the world with such a national ban.

Immediately after, ESDO—as a founding member of GAIA—launched a national anti-incineration campaign. The organization has since launched many other campaigns, including mercury-free dentistry, Zero Waste, and a ban on single-use plastics, among others.

Meanwhile, GAIA, despite experiencing some ups and downs, has grown immensely, becoming a strong global network, especially in recent years. In 2016, it gave birth to the global movement Break Free From Plastic (BFFP) together with partner organizations.

Looking back, Dr. Shahriar can’t help but feel emotional thinking about what GAIA has become, and what it has achieved. “We have obsoleted the idea of incineration. We have put forward the idea of Zero Waste communities. We have established that if we want to have sustainable waste management, we have to move towards Zero Waste,” he said.

He also considers the birth of BFFP as among the network’s major achievements. “We thought about it in 2013. We thought of having a space that welcomes ideas even from those who are not members of GAIA, and it’s thanks to Christie (Keith, GAIA InternationalCoordinator) for taking the idea and moving it forward,” he said.

Now a strong global movement, BFFP has campaigned, among other things, for the same thing that got him exiled and almost killed nearly 30 years ago—ban on plastic bags—and the movement has had major successes. Single-use plastics are now banned in many cities and countries around the world.

For Dr. Shahriar, it’s coming full circle. “My feeling is, we just crossed a hurdle towards a SUP-free planet, and that the war I started with a single issue of plastic bags was a starter to achieve my vision of a plastic-free world,” Dr. Shahriar said.

Although he has been fortunate to see successes in his advocacy, Dr. Shahriar believes that the work of an activist never ends.